Haḍḍa Archeo Database Project

Haḍḍa is the name of a modern village in Afghanistan located twelve kilometres south of the present-day city of Jellālābād, built on the ruins of a small pre-Islamic town on which depended a large Buddhist monastic complex that flourished during the early centuries of the Christian era. The saṃgharama of Haḍḍa were among the great religious centres that hosted Buddhist pilgrims travelling along the Silk Road between India and China through Gandhāra. Located at the gateway to India and believed to have housed some of the relics of Buddha Cakyamuni, these flourishing monasteries were inhabited by generations of monks and visited by as many Buddhist devotees until the 9th century CE. Around the time of the Ghaznevid era, the saṃgharama were sacked and destroyed by a widespread fire.

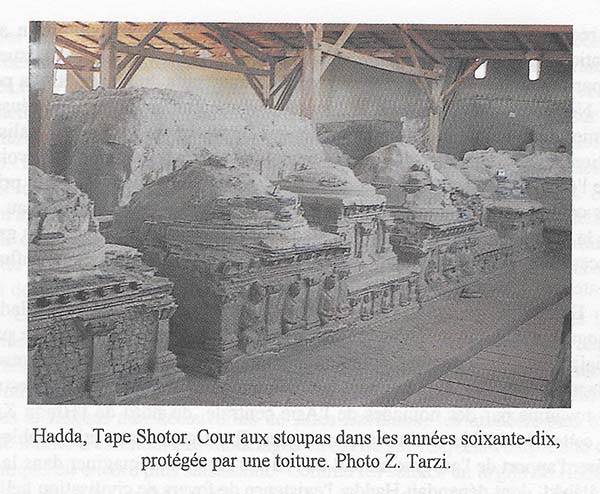

Forgotten for eight centuries, the site was rediscovered in 1825 during the exploratory missions of General Court. His findings, as well as those of his successors, Charles Masson for the East India Company (1841) and William Simpson (1879), led to the discovery of numerous works of art and ancient coins attesting to the long period of activity of the monasteries. Archaeological missions began in the following century, led by the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan. The site, prospected by Sir Alfred Foucher and André Godard in 1923, was extensively excavated by Jules Barthoux between 1926 and 1933 at Tapa Kalān ("the Great Hill"), Bāgh Gaï, Gār Naô, Pratès, Chakhil-i Ghoundi, Deh-i Ghoundi and Tapa-i Kafarihā, and then by Seiichi Mizuno for Kyoto University between 1963 and 1965 at Lalma. The newly created Afghan Institute of Archaeology commissioned Shaïbaï Mostamindi to excavate Tapa-e Shotor ("The Camel Hill") from 1965 to 1972. Following him, Zemaryalai Tarzi continued the study of Tapa-e Shotor from 1973 to 1979, and excavated Tape Tope Kalān from 1977 to 1979. From the first excavations conducted by Barthoux, a dozen monasteries, dozens of chapels and as many stūpa decorated with thousands of modelings and sculptures were discovered and studied. The artistic production of the Haḍḍa school, exceptional for its aesthetic quality, the liveliness of its western inspirations and its preferred mediums, stucco and clay, shed a different light on the multiple faces of Gandhāra art from that time onwards.

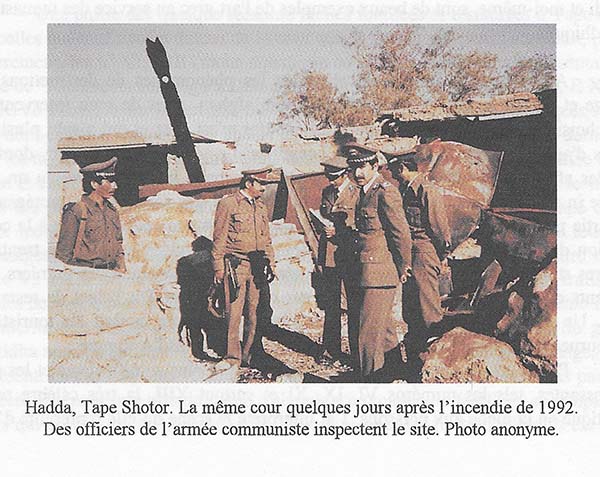

The site was partly preserved and protected by Prof. Tarzi in the 1970s. Unfortunately, due to the political tensions under the communist regime, the archaeological study had to be interrupted and the conflicts led to the burning and destruction of the site in 1992.

The site was partly preserved and protected by Prof. Tarzi in the 1970s. Unfortunately, due to the political tensions under the communist regime, the archaeological study had to be interrupted and the conflicts led to the burning and destruction of the site in 1992.

Now razed to the ground, nothing remains of its former prosperity.

Now razed to the ground, nothing remains of its former prosperity.

We see this all too regularly, with whole swathes of the world's cultural heritage disappearing in the wake of modern conflicts. These priceless losses afflict us and reveal the absolute necessity to reflect collectively on the different ways to work towards the conservation of endangered heritage, but also to safeguard the data relating to the lost heritage. One of the means at our disposal is the computer tool and in recent years many digitisation projects have been launched, with the aim of enhancing the value of the heritage, preserving archaeological data and making them accessible. It is in this context that the Haḍḍa Archéo Database project was born. On the one hand, we have an abundance of documentation collected as a result of archaeological excavation campaigns. On the other hand, material has been preserved, and hundreds of modellings, dozens of sculptures and some paintings and secondary stūpa have been kept in the shelter of several museums. The aim of the Haḍḍa Archéo Database project is to perpetuate the memory of the artistic and archaeological heritage of the Haḍḍa monasteries and to make the scientific data accessible to colleagues and students in order to facilitate comparative study as well as the examination of artistic influences and iconographic themes. The transmission of this knowledge will lead to a better understanding of the relationships and chronology of artistic production in the different regions of Gandhāra, and can serve as a basis for more extensive comparative studies. Furthermore, it is essential to give the Afghan people, their scholars and students access to archaeological and cultural knowledge relevant to their own history. This sharing and scientific exchange cannot be fruitful without being multilingual. The data will therefore be translated into Dari as soon as possible. The translation of the site into English is already underway. The first stage of the data entry consisted in putting online the works discovered during the first series of archaeological excavations carried out by Jules Barthoux between 1926 and 1933 at the request of Alfred Foucher. A second stage will see the addition of works from the excavations of Prof. Mizuno at Lalma, Prof. Mostamindi at Tapa-e Shotor, and the published discoveries of Prof. Tarzi at Tapa-e Shotor and Tapa Top-e Kalān, as well as the addition of works dispersed in museums and private collections. In a third phase, the works discovered by Prof. Z Tarzi, still unpublished to date, will be added.